Background

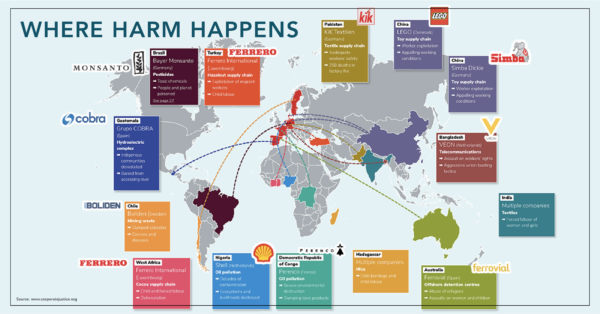

Businesses commit human rights abuses and environmental damage through their global operations or along their supply chains. The clothing industry has been among the most prominently associated with human rights abuses. Horror stories of labour exploitation in developing countries regularly emerge implicating popular brands like Spain’s Zara and Germany’s Adidas.

The Rana Plaza tragedy, which in 2013 killed 1,138 textile workers in Bangladesh, is emblematic of the pain and suffering businesses can cause in the name of profit.

The textile industry is not unique though. Violators span all sectors. Luxembourg-headquartered Ferrero International, makers of Ferrero Rocher and Nutella, have been found to source their raw materials, cocoa and hazelnuts, from plantations that employ children and migrant workers paid below minimum wage.

German agribusiness Bayer-Monsanto has been accused of poisoning thousands in Brazil’s rural communities with its pesticides. The EU’s Agency for Fundamental Rights admits that victims of corporate abuse rarely find justice.

Campaigners have long demanded binding rules to force businesses to respect human rights and protect the environment. Existing legislation is inadequate, there is poor enforcement and victims are rarely afforded justice.

The EU now intends to introduce compulsory supply chain due diligence for businesses. This is but a small step towards ending business involvement in human rights violations and environmental crimes.

The failure of voluntary initiatives

Businesses have promoted self-regulation initiatives under catch-all Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). The world’s largest corporations put a lot of effort in promoting positions of support for human rights, the environment and ethics.

However, very often, these end up being exercises in corporate whitewashing that delay regulation and justice. Shell for example has been accused of complicity with murder, rape and torture, among other abuses in the countries it operates. The company features human rights prominently on its website.

Likewise, the United Nations hosts two voluntary initiatives. The UN Global Compact encourages companies to adopt sustainable and socially responsible practices, while the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights focuses on respect for human rights. While helping to raise the profile of these issues in the international stage, these tools have had limited impact in actually stopping violations or holding perpetrators to account.

Corporate accountability

Campaigners are leading efforts for a UN Binding Treaty for Transnational Corporations on Human Rights. The EU and the US have been the main blockers of this initiative.

In the absence of government action, grassroots mobilisations have, at times, succeeded in ending corporate abuses. French company Veolia was forced to divest its operations from Israel after sustained campaigning. Activists exposed its business dealings in illegal Israeli settlements, including the running of a segregated bus services for settlers. The company suffered reputational damage and lost lucrative contracts as a result.

Recently, Shell was ordered by a Dutch court to pay compensation to Nigerian farmers for polluting their land. While promising, these success stories are few and far in between

An EU corporate due diligence directive, while short of what is needed, puts a welcome spotlight on human rights violations, environmental crimes and governance malpractice in companies’ value chains. How far will the directive go into holding businesses to account? Would “due diligence” absolve corporations of responsibility further down the line? Would victims have access to redress in EU courts?

The Right is working hard to dilute the directive by exempting some companies and weakening its liability provisions thus turning it into a formality with weak enforcement or results.

The view of the Left

The Left believes that corporations must be held accountable for their crimes and victims must access justice. The EU must stop blocking a binding international treaty.

Meanwhile, an EU due diligence directive must be broad to be effective, applying to all multinationals with presence in the EU, and span the entire supply chain, not just direct suppliers. Victims must have access to EU courts, being able to sue businesses for environmental and human rights violations committed in their countries.

Finally, offenders must face sanctions including criminal liability and heavy fines, prevented from receiving public aid and barred from participating in public tenders